News-Pheasants

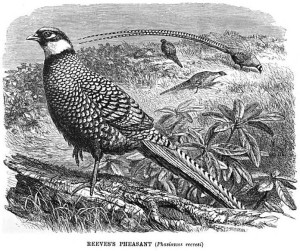

Reeves’s Pheasants

“Pheasants: Their Natural History and Practical Management” By William Bernhard Tegetmeier

Not only in the extreme north, but in the more cultivated parts of England, Reeves’s pheasants have done well. One gentleman informs me that during the year 1895 he raised more than twenty in the open, which are now all in full plumage, and that he found them easy to rear.

There can be no doubt whatever, as suggested by Lord Lilford, that, the bird being from North China, is hardy and well adapted to mountainous districts, such as those of Scotland and Wales. It appears that the easiest way of introducing it as a wild bird in those places to which it is adapted would be to place the eggs in the nests of pheasants breeding in the open. Reared under those circumstances, the young would be hardy and vigorous in the extreme, and would be much more likely to do well than if hand-reared and turned out afterwards. The fact of the hybrids between it and the common species being sterile is, to my mind, rather in its favour than otherwise. There would be no mongrel crosses introduced, and Reeves’s pheasant could be confined to those regions to which by its size and habits it is specially adapted. With regard to its beauty and magnificence there can be no doubt, and Lord Lilford speaks practically as to its value as a bird for the table, but I have never had the opportunity of testing its value in this respect.

The most important communication respecting the value of the Reeves’s pheasant as a game bird, and its rearing in the forests of mountainous districts, was made to the Field on February 9, 1896, by Mr. J. G-. Millais. This was accompanied by a most graphic sketch of the flight of the bird, which Mr. Millais has kindly given me permission to reproduce. Mr. Millais’s letter is as follows:

“I noticed a letter by Mr. Tegetmeier in the Field of January 25, on the desirability of establishing Reeves’s pheasant as a British game bird; and as I have seen and shot several of these birds at home, perhaps my observations on the species may be of some interest.

“There is no game bird, I think, in the world, which, if introduced into suitable localities, would give greater pleasure to both the sportsman and the naturalist than this grand pheasant; for grand he certainly is, both to the eye as well as the object of aim to the expectant shooter. We all know, when a cock Reeves’s pheasant attains his full beauty and length of tail, what a splendid bird he is as he struts about in his gorgeous trappings, and shows himself off for the benefit of his lady-love, but when the same bird is launched in the air, and dashes along above the highest trees of a wild Scotch landscape, leaving poor old Colchicusto scurry at what seems but a slow pace behind him, I can assure your readers that both the dignity and the pace arealike wonderful, and a sight not easily to be forgotten.

“Until the year 1890 I had seen and shot several Reeves’s pheasants, and under ordinary conditions of covert shooting was content to consider the bird hardly a success from a gunner’s point of view. During that autumn, however, I went to the annual covert shoot at Guisachan, Lord Tweed mouth’s beautiful seat, near Beauly, in Ross-shire, and it was there, amidst the wildest and shaggiest of Scotch scenery— in country which must to a great extent resemble the true home of the bird in question—that I had cause to alter my opinion.

“In one high wood of old Scotch firs, on a steep and broken hillside above the waterfall, the sight of these birds coming along only just within gunshot, in company with common pheasants and blackcocks, I shall never forget. I say, ‘in company with,’ but, as a matter of fact, as soon as one of the long-tailed sky-rockets cleared the trees, he left the others far behind, and came forward at a pace which was little short of terrific I doubt if any bird of the genus goes faster.

“Now, this is all that the sportsman wants. Here we have a bird of unrivalled beauty, great hardihood, and unequalled pace, which practically fulfils all the conditions which the modern shooter requires. The only other condition which is absolutely essential to make the bird a success from this point of view is its local environment. In this respect Guisachan is not singular, and I could name a hundred localities in Scotland, England, and Wales where Reeves’s pheasant would be certain to succeed.

“The Guisachan birds were obtained by the late Lord Tweedmouth from Balmacaan, the late Lord Seafield’s estate near Loch Ness, where I have also seen them shot. No artificial rearing was resorted to; the birds were breeding in a wild state, and shifting entirely for themselves, except for the maize which was put down for the ordinary pheasants. At Balmacaan, where the birds were in low open woods, one may see Reeves’s pheasants killed in the way in which they should not be. Here these birds (as is the case when turned down on any ordinary English preserve) have formed most undesirable habits. It is with great difficulty they can be got to rise at all, and when this is effected they keep low, and afford no sport whatever. Now, at Guisachan all this is obviated by the rough nature of the ground. There is heavy bracken, fallen trees, mountain burns, and, above all, rough heather. These causa the birds to get up almost at once. The trees being high and dense assist their elevation, and force them to a respectable height from the very start.

“In conclusion, I should like to make one observation on the flight of Reeves’s pheasant which I have never seen touched on before, and which is both interesting and remarkable. Reeves’s pheasant has the power to stop suddenly when travelling at its full speed, which may be estimated at nearly double that of an ordinary pheasant; and this is performed by an extraordinary movement when the bird makes up its mind to alight on some high tree that has taken its fancy. This bird may be said to be furnished with a ‘Westinghouse brake’ in the shape of its tail, otherwise the feat would be impossible. By a sudden and complete turn of the body, both the expanded wings and tail are presented as a resistance to the air, and the position of the bird is reversed. This acts as an immediate buffer and brake, and by this means the bird is enabled to drop head downwards into the tree within the short space of eight or ten yards. This is such a very remarkable movement, and one which of necessity requires some illustrative explanation, that I send you herewith a sketch of it, which may be of interest.”